Mental Health and Care in Mainland China: Apps filling the gap?

By: Vince Alessi, April 14th 2021

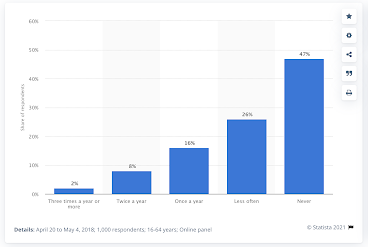

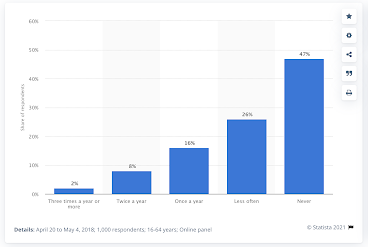

Mental health has historically been a highly stigmatized topic in developing nations that have recently undergone rapid transitions from being labeled a '3rd world' to a '1st world nation'. There are several examples of this, albeit predominantly in sino-eurasian nations. Historically, China has been amongst the most outwardly intolerant of mental health illness as comparable to more demonstrable physical maladies. In 2011, a study performed by Whittington and Higgins indicated that the majority of Chinese nurses in nationally supported hospitals exhibited minimal or "zero-tolerance" for multiple behaviors commonly associated with one or more mental illness. Even to do this day, overall the Chines population does not engage in mental health services or make visits to a care provider with any frequency, as shown in the figure.

Over the years, however, as the class structure of mainland has led to appearance of a robust middle class, appreciation and sensitivity towards mental health issues have improved. This is largely ascribed to the transition away from 'working class' mental illnesses, usually considered to largely be comprised of substance abuse, addition, schizophrenia, and other forms of illness that categorically impair an individuals ability to contribute to society. Something anathema to collectivist society perspectives on an individual's value. This trend is reflected in epidemiological studies.

A survey of a ~35,000 population of individuals curated to be representative of China at large was performed by Huang et al in Lancet Psychiatry in 2019. They found that "The prevalence of most mental disorders in China in 2013 was higher than in 1982 (point prevalence 1·1% and lifetime prevalence 1·3%), 1993 (point prevalence 1·1% and lifetime prevalence 1·4%), and 2002 (12-month prevalence 7·0% and lifetime prevalence 13·2%), but lower than in 2009 (1-month prevalence 17·5%)." This increase from 1.3% to 13.2% is a 10x increase in 20 years is without similar comparison any rest in the world. The prevalence estimate in 2009 of 17.5% in comparison may appear significant, however in a global context it is not: according to a study performed by Kessler et al and published in 2010 by World Psychiatry found that the 2009 number of 17.5% is in fact the lowest reported prevalence of mental health disorders amongst the worlds top 16 most economically developed nations. Middle class mental health disorders are comparatively on the rise, including such disorders as bipolar and major depression, anxiety disorders, ADHD, and conduct/personality disorders. One of the signs that there is a growing appreciation for mental health is the self-assessment by Chinese citizens on what most contributes to their happiness.

In stark comparison to classically accepted family-first values of nuclear Chinese families, this survey would indicate that personal mental health is in fact the #1 concern of an individual. However, the mental health services infrastructure in china is underdeveloped, and though purportedly covered by state health insurance, the associated quality care has been such that minimal adoption as occurred.

A silver lining in this story is that digital services have found home in serving the blossoming mental health needs of the Chinese people. Although indicating only a fraction of the overall population uses these services, when taken in context that there are ~900M cell phones in china, it indicates the 2.5-3.3% of the population have downloaded and presumptively use these services. This is only slightly less than the ~4% of cell phone owners who have fitness apps.

However, based on the WHO estimation of there are over 90,000,000 Chinese citizens suffering from anxiety or depression. Assuming that all ~30M mental health apps users are included in these 90M individuals, it still leaves ~66% of individuals putatively without easily accessible care; access to in-person mental health care has been massively impaired by COVID. While the central Chinese government promises that at least "80% of patients suffering from depression will have access treatment by 2030 (and at least 30% by 2022), based on public targets from the 'Healthy China 2019-2030' program, there is great skepticism regarding its ability to serve a patient population that is project to be near 300M individuals by that time." There is no doubt that digital service technologies will be required within the process of delivering mental health care.

The use of digital applications to serve mental health needs provides a promising vector for meeting the growing unmet need for mental health services. However, concerns over efficacy of these platforms remain, as well as access to phones needed to connect to these services. The pressing need for services in the mental health area will, however, continue to drive innovation and novel therapeutic approaches that the global mental health community will be able to learn from. China's current conundrum with their emerging mentally ill population may provide either a best-practices case study, cautionary tale, or something in-between, to many developing nations on the cusp of transitioning to a '1st world' country status and developing the unique burdens associated with the middle class which comes along with it.

Reference and Source:

- Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168-176.

- Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Mar;6(3):211-224. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X. Epub 2019 Feb 18. Erratum in: Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;6(4):e11. PMID: 30792114.

- Whittington, R. and L. Higgins. “More than zero tolerance? Burnout and tolerance for patient aggression amongst mental health nurses in China and the UK.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 106 (2002):

- DXY.cn; Sina.com.cn

- Statista.Com

- World Health Organization

Comments

Post a Comment